Functions, Arrays and Structs

Learning Outcomes

After reading this section, you will be able to:

- Design procedures using selection and iteration constructs to solve a programming task

- Connect procedures using pass-by-value and pass-by-address semantics to build a complete program

- Design data collections using arrays and structures to manage information efficiently

- Trace the execution of a complete program to validate its correctness

Introduction

Procedural programming scopes information. Scoping is an essential feature of modular design. A complete program consists of a variety of scopes. Each module limits the visibility of the program data and instructions in that module. Each code block limits the visibility of the data in that block.

This chapter describes how to identify a function type, describes the different scopes within a program, describes the passing of arrays and structures to a function, lists style guidelines for function coding and provides a sample walkthrough with functions, pointers and structures.

Prototypes

A function prototype identifies a function type. It provides the information that the compiler requires to validate a function call. The prototype is similar to the function header. A prototype takes the following form

type identifier(type [parameter], ..., type [parameter]);

A prototype ends with a semi-colon and may exclude the parameter identifiers. The identifier, the return type, and the parameter types are sufficient to validate a function call. The parameter types determine any coercion that may be necessary in passing values to the function.

For example, the prototype for our power() function in the chapter entitled Functions is:

int power(int, int);

We insert prototypes near the head of our source file and before any function calls. Once we have declared the prototype for each function in a source file, we can arrange our function definitions in any order.

For example:

/* Raise an integer to the power of a integer

* power.c

*/

#include <stdio.h>

int power(int base, int exponent);

int main(void)

{

int base, exp, answer;

printf("Enter base : ");

scanf("%d", &base);

printf("Enter exponent : ");

scanf("%d", &exp);

answer = power(base, exp);

printf("%d^%d = %d\n", base, exp, answer);

return 0;

}

int power(int base, int exponent)

{

int result, i;

result = 1;

for (i = 0; i < exponent; i++)

{

result = result * base;

}

return result;

}

The compiler interprets the call to power() in the main() function as a valid call based on the prototype (not the header in the function definition below the call).

include

We can define a function used by our host application in a file separate from the source file of our application. If we do, we also store its prototype in a separate file called a header file. Typically, this header file has the extension .h. We insert the contents of the header file into the source file of our application using a #include directive.

The #include directive takes either of two forms:

#include <filename> // filename is in the system directories

#include "filename" // filename is in the current directory

The compiler searches for the header file in the current directory, the system directory or both and, if found, inserts the contents of the file in place of the directive.

stdio.h

The header file that contains the prototypes for the printf() and scanf() functions is called stdio.h and is stored in a system directory.

We include this header file in our source code whenever we call either of these functions:

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void)

{

printf("This is C\n");

return 0;

}

Current Directory(Optional)

We may store the prototype for our power() function in its own header file (.h) and insert that header file in our source code. For example:

/* Raise an integer to the power of a integer

* power.h

*/

int power(int base, int exponent);

The corresponding implementation file (.c) will look like:

/* Raise an integer to the power of a integer

* power.c

*/

#include <stdio.h>

#include "power.h"

int main(void)

{

int base, exp, answer;

printf("Enter base : ");

scanf("%d", &base);

printf("Enter exponent : ");

scanf("%d", &exp);

answer = power(base, exp);

printf("%d^%d = %d\n", base, exp, answer);

return 0;

}

int power(int base, int exponent)

{

int result, i;

result = 1;

for (i = 0; i < exponent; i++)

{

result = result * base;

}

return result;

}

Scope

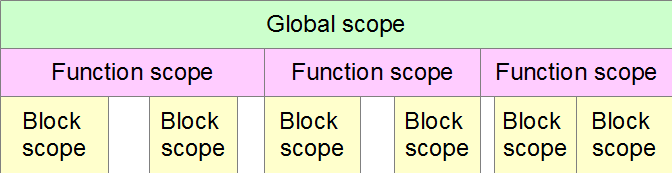

The scope of a program identifier determines its visibility. Its scope depends on where we have placed its definition. A program variable may have

- global scope

- function scope

- local scope

- block scope

Global Scope

A variable declared outside all function definitions has global scope. We call such a variable a global variable. Any program instruction can access a global variable. The compiler allocates memory for a global variable alongside the string literals at startup and releases that memory at termination; that is, after having executed the return statement of main().

Global variables introduce a high degree of coupling. For instance, if we change the name of the variable in its definition, we need to change it in all functions that reference that variable. Because of this high degree of coupling, we avoid global variables altogether. Their presence complicates maintainability: if 1000s of functions reference the variable, changing its name proves to be a major undertaking and can lead to mistakes introducing bugs into the program.

Function Scope

A variable that we declare within a function header has function scope. We call such variables function parameters. The scope of the parameter extends from the function header to the closing brace of the function body. We say that the parameter goes out of scope at this closing brace.

The compiler allocates memory for a function parameter when the function is called and releases that memory when the function return control to its caller. C compilers initialize the values of the function parameters to the values of the arguments in the function call.

Local Scope

A variable that we declare within a function body has local scope. We call such variables local variables. The scope of the variable extends from its definition to the end of the code block within which we declared the variable. We say that the variable goes out of scope at the closing brace of its code block.

The compiler allocates memory for a local variable where it is defined (or first used) and releases that memory when the variable goes out of scope. C compilers do not initialize the values of local variables.

Block Scope

A variable that we declare within a code block has block scope. The scope of the variable extends from its definition to the end of the code block within which we declared the variable. We say that the variable goes out of scope at the closing brace of its code block.

Overlapping Scope (Optional)

A variable occupies its own memory location from its declaration to the end of its parent code block. We refer to this period as the variable's lifetime. A variable is visible throughout its lifetime as long as it is not hidden by another variable of the same name.

Consider the following program. The variable x within the code block hides the local parameter x until the end of the iteration.

/* Avoid Variables of the Same Name

* lifetime.c

*/

#include <stdio.h>

void foo(int x)

{

int i = 4;

do {

int x = i;

printf("%d ", x);

i--;

} while(i > 0);

printf("%d ", x);

}

int main(void)

{

foo(6);

return 0;

}

The program above will produce the following output:

4 3 2 1 6

We say that the x declared within the code block shadows the parameter x declared in the function header.

Using the same name for two distinct variables with overlapping lifetimes only introduces confusion. Although compilers accept such code, it is poor style and best avoided altogether.

Passing Arrays

The elements of an array occupy contiguous locations in memory. Because of this accessing any element from within a function only requires the address of the start of the array and the element index.

The name of an array without the brackets holds the address of the start of the array.

Array Arguments

To grant a function access to an array, we pass the array's address as an argument in the function call. The call takes the form

function_identifier(array_identifier, ... )

By passing the address, we avoid copying the entire array. The decision to pass arrays in this way was made when the C language was designed.

For example:

// Passing an Array to a Function

// passArray.c

#include <stdio.h>

#define NGRADES 8

// definition of display() ...

int main(void)

{

int grade[] = {10,9,10,8,7,9,8,10};

display(grade, NGRADES);

return 0;

}

Parameters

A function header that receives an array's address takes the form:

type function_identifier(type array_identifier[], ... )

or

type function_identifier(type *array_identifier, ... )

The empty brackets following identifier in the first alternative tell the compiler that the parameter holds the address of a one-dimensional array. For example:

// array using []

void display(int g[], int n)

{

for(i = 0; i < n; i++)

{

printf("%d ", g[i]);

}

}

OR:

// array using * (pointer)

void display(int *g, int n)

{

for(i = 0; i < n; i++)

{

printf("%d ", g[i]);

}

}

Because we have passed the address of the array and not a copy of all of its elements, any change to an element within the function will change the array element in the caller.

Barring Changes

To prevent a function from changing any element of an array identified by a function parameter, we qualify the parameter as const. The function header takes the form:

type function_identifier(const type array_identifier[], ... )

OR:

type function_identifier(const type *array_identifier, ... )

For example:

// array using []

void display(const int g[], int n)

{

for(i = 0; i < n; i++)

{

printf("%d ", g[i]);

}

}

OR:

// array using * (pointer)

void display(const int *g, int n)

{

for(i = 0; i < n; i++)

{

printf("%d ", g[i]);

}

}

Any attempt to modify the value of an element of

gwill generate a compiler error. Without theconstkeyword, we could reset the value of the first element to 10 by adding a statement likeg[0] = 10;.

Passing Structures

We can pass an object of structure type to a function in either of two ways:

- pass by value

- pass by address

Consider the following program. Note that the Student structure includes a member that identifies the number of grades filled. We pass harry as a single argument to display() and access its member within the function:

// Passing a structure to a function

// pass_by_value.c

#include <stdio.h>

struct Student

{

int no;

int noGradesFilled;

float grade[4];

};

void display(const struct Student s); // pass by value

int main(void)

{

struct Student harry = {975, 3,

{75.6f, 82.3f, 68.9f, 0.0f}};

display(harry);

}

void display(const struct Student st)

{

int i;

printf("Grades for %d\n", st.no);

for (i = 0; i < st.noGradesFilled; i++)

{

printf("%.1f\n", st.grade[i]);

}

}

The above program produces the following output:

Grades for 975

75.6

82.3

68.9

The declaration of Student precedes the prototype for display(). The compiler needs this declaration to interpret the parameter type in the prototype.

The C compiler passes objects of structure type by value. It copies the value of the argument in the function call into the parameter, as its initial value. Any change within the function affects only the copy and not the original value.

In the following example, the data stored in harry does not change after the function set() returns control to main():

// Pass by Value

// pass_by_value.c

#include <stdio.h>

struct Student

{

int no;

int noGradesFilled;

float grade[4];

};

void set(struct Student st);

void display(const struct Student st);

int main(void)

{

struct Student harry = { 975, 2, {50.0f, 50.0f}};

set(harry);

display(harry);

}

void set(struct Student st)

{

struct Student harry = {306, 2, {78.9, 91.6}};

st = harry;

}

void display(const struct Student st)

{

int i;

printf("Grades for %d\n", st.no);

for (i = 0; i < st.noGradesFilled; i++)

{

printf("%.1f\n", st.grade[i]);

}

}

The above program produces the following output:

Grades for 975

50.0

50.0

The values in the original object, its copy and the local object are shown in the table below:

int main() | void set() | |

struct Student harry | struct Student st | struct Student harry |

| 975 2 50.0f 50.0f | 975 2 50.0f 50.0f | |

| 975 2 50.0f 50.0f | 975 2 50.0f 50.0f | 306 2 78.9f 91.6f |

| 975 2 50.0f 50.0f | 306 2 78.9f 91.6f | 306 2 78.9f 91.6f |

Copying

The C compiler performs member-by-member copying automatically whenever we:

- pass an object by value

- assign an object to an existing object

- initialize a new object using an existing object

- return an object by value

- pass by address

To change the data within an original object passed to the set() function, we require the address of the original object. In the call to set() we pass its address. set() receives this address in its pointer parameter.

In the following program, we pass the address of harry to set():

// Pass by Address

// pass_by_address.c

#include <stdio.h>

struct Student

{

int no;

int noGradesFilled;

float grade[4];

};

void set(struct Student* st);

void display(const struct Student st);

int main(void)

{

struct Student harry = { 975, 2, {50.0f, 50.0f}};

set(&harry);

display(harry);

}

void set(struct Student* st)

{

struct Student harry = {306, 2, {78.9, 91.6}};

*st = harry;

}

void display(const struct Student st)

{

int i;

printf("Grades for %d\n", st.no);

for (i = 0; i < st.noGradesFilled; i++)

{

printf("%.1f\n", st.grade[i]);

}

}

The above program produces the following output:

Grades for 306

78.9

91.6

The values in the original object and the local object are shown in the table below:

int main() | void set() | void display() | |

struct Student harry | struct Student *st | struct Student harry | struct Student st |

| Address: 22ff2b8d4 | 22ff2b8ec | 22ff2b8f0 | 22ff2b908 |

| 975 2 50.0f 50.0f | |||

| 306 2 78.9f 91.6f | 2ff2b8d4 | 306 2 78.9f 91.6f | |

| 306 2 78.9f 91.6f | 306 2 78.9f 91.6f | ||

Efficiency

Passing an object by address is efficient. It avoids copying all member values, saving time and space especially in cases where a member is an array with a large number of elements. Passing an object by address only copies the address, which typically occupies 4 bytes.

Consider passing harry by address to function display() as well:

// Pass by Address 1

// pass_by_address_1.c

#include <stdio.h>

struct Student

{

int no;

int noGradesFilled;

float grade[4];

};

void set(struct Student* st);

void display(const struct Student* st);

int main(void)

{

struct Student harry = { 975, 2, {50.0f, 50.0f}};

set(&harry);

display(&harry);

}

void set(struct Student* st)

{

struct Student harry = {306, 2, {78.9, 91.6}};

*st = harry;

}

void display(const struct Student* st)

{

int i;

printf("Grades for %d\n", (*st).no);

for (i = 0; i < (*st).noGradesFilled; i++)

{

printf("%.1f\n", (*st).grade[i]);

}

}

The above program produces the following output:

Grades for 306

78.9

91.6

display() dereferences the address before selecting the members. Since the dot operator binds tighter than the dereferencing operator, the parentheses are necessary. Omitting them would generate a compiler error (the data member after the dot operator is not of type Student*).

If we pass by address with no intention of changing that object within the function, we add the const qualifier to safeguard against accidental modifications.

The values in the original object and the local object are shown in the table below:

int main() | void set() | void display() | |

struct Student harry | struct Student *st | struct Student harry | const struct Student *st |

| Address: 22ff2b8d4 | 22ff2b8ec | 22ff2b8f0 | 22ff2b908 |

| 975 2 50.0f 50.0f | |||

| 306 2 78.9f 91.6f | 2ff2b8d4 | 306 2 78.9f 91.6f | |

| 306 2 78.9f 91.6f | 2ff2b8d4 | ||

Arrow Notation

The syntax (*s).no is awkward to read. Arrow notation provides cleaner alternative. It takes the form:

address->member

The arrow operator takes a pointer to an object on its left and a member identifier on its right.

For example:

// Pass by Address 3

// arrow_notation.c

#include <stdio.h>

struct Student

{

int no;

int noGradesFilled;

float grade[4];

};

void set(struct Student* st);

void display(const struct Student* st);

int main(void)

{

struct Student harry = { 975, 2, {50.0f, 50.0f}};

set(&harry);

display(&harry);

}

void set(struct Student* st)

{

struct Student harry = {306, 2, {78.9, 91.6}};

*st = harry;

}

void display(const struct Student* st)

{

int i;

printf("Grades for %d\n", st->no);

for (i = 0; i < st->noGradesFilled; i++)

{

printf("%.1f\n", st->grade[i]);

}

}

The above program produces the following output:

Grades for 306

78.9

91.6

Style

The rules of structured programming extend directly to functions. A structured program does not have multiple returns. We replace multiple return statements with flags logic and a single return statement.

It is good programming style to:

- place the opening brace on a separate line

- declare a prototype for each function definition

- include parameter identifiers in the prototype declaration as documentation

- use generic comments and variables names to enable future use in different applications without having to modify any of the function code

- avoid calling the

main()function recursively - limit the number of local variables to below 10, if possible

- adhere to the single-entry single-exit principle having a single return statement

Documentation

We document each function at one level of abstraction above the caller. We precede the function header in the function definition with comments that describe:

- what the function does (not how)

- what the function needs (in terms of values for its parameters)

- what the function returns (if anything)

We state any assumption or constraint that applies to using the function.

For example:

// power returns the value of base raised to

// the power of exponent (base^exponent)

//

// power assumes that base and exponent are

// integer values and exponent is non-negative

//

int power(int base, int exponent)

{

int result, i;

result = 1;

for (i = 0; i < exponent; i++)

{

result = result * base;

}

return result;

}

Structure Walkthrough

The following program contains several objects of type A. The walkthrough table is shown below.

// Structure Types - Walkthrough

// struct_walk.c

#include <stdio.h>

struct A

{

int x;

double r;

};

void foo(struct A* c);

struct A goo(struct A d);

int main(void)

{

struct A a = {4, 6.67}, b;

foo(&a);

printf("00%d.%.3lf.111\n", a.x, a.r);

b = goo(a);

printf("00%d.%.3lf.112\n", a.x, a.r);

printf("%d.%.3lf.113\n", b.x, b.r);

}

void foo(struct A* c)

{

int i;

i = c->x;

c->x = c->r;

c->r = c->x % i + 202.134;

}

struct A goo(struct A d)

{

struct A e;

d.x = d.r - 62;

e = d;

return e;

}

The table includes:

- the return type for each function

- the name of each function

- the structure type of each object

- the name of each object

- the type of each member

- the name of each member

The breakdown of each object into its members in the head of the table. We reserve a separate line for the addresses that are pointed to:

int | void | struct A | |||||||

main() | foo() | goo() | |||||||

struct A | struct A | struct A* | struct A | struct A | |||||

| a | b | c | d | e | |||||

| Address: 1000 | 100C | 1018 | 101C | 1020 | 102C | ||||

| int | double | int | double | int | int | double | int | double | |

| x | r | x | r | i | x | r | x | r | |

| 1000 | |||||||||

| 1000 | |||||||||

| 1000 | |||||||||

| 1000 | |||||||||

| 1000 | |||||||||